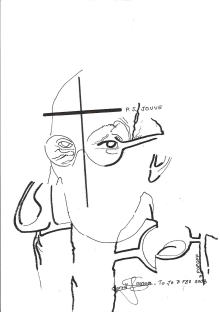

Jouve

International

Domaine anglais

par Serge Popoff

Life

with the Jouves 1936 - 1940

See also :

(1) The Fall of Paris

and the presentation of the characters

(2) Au Pays des Merveilles

by Isabel Ryan

Excerpt

from

Isabel Ryan Chronicles Vol 1

France 1936 - 1940

Isabel Ryan first met the Jouves at the Salzburg music festival in 1936. Aged 21, she had been entrusted to their care by her mother, a South African Scot. Blanche wanted to observe Isabel and see if she could help her with her nervous and spinal problems. It was a test really to see if Isabel would benefit by being away from her mother and how she would react to Blanche’s cultured, European circle. It was to be an extraordinary and ultimately life-changing experience.

We went to visit Mme Jouve in Paris. She said would be interested to diagnose me, but she was just leaving for the summer Salzburg festival. She and her husband would reserve a room for me in the house where they were staying and she would be able to observe me and give an opinion.

Did Gran go with you to Salzburg?

No, and that was the wonderful thing. That’s why Blanche took me into the house because otherwise I wouldn’t have been allowed to go. The thing was to get me away from mother.

So Blanche spotted pretty quickly that Gran was reluctant to let you go?

Oh she did, she spotted it. Mother’s mother died when I was two, in the middle of the 1st World War. She felt terribly bereft of the other woman that she had been attached to and she expected me to be as attached to her as she was to her mother. Mother was an only child and in a new town; they were pioneers in Durban. She and her mother were very close. Her husband was a much older man who had been a friend of her mother’s rather than her own.

Salzburg was a complete eye-opener for me because there was no classical music going on in Durban in those days. It was marvellous, and another language, because French I had learnt at school but German I didn’t know. I slept in the same house as Pierre and Blanche but they ate out and took their meals in the continental fashion so I had to feed myself, and life for a young girl on her own is a bit of a battle: you get picked up and accosted. So Blanche arranged for me to go to a family for meals.

I didn’t know anything about going to the festival concerts, and Blanche advised me to go to Don Giovanni, it was the big one that year, Bruno Walter conducting. She said ‘Oh yes, Monique Haas, she’s a musician, she’ll take you to buy the tickets’. She gets a famous concert pianist to take me to buy a ticket to a concert!

At the Conservatoire in Paris Monique had met and married the Romanian-born Mihailovic who was a composer. He was not having much success; she was doing much better so their marriage was a little difficult. They were having problems with the situation of his composing and she went to Blanche. Blanche had a poet-writer as a husband and she understood the problems of balancing a career and an artistic husband.

Another person I met was Consuelo de St Exupéry, St Exupéry’s wife‡. She came from San Salvador. He was an aviator, flying open planes in South America. She was very beautiful, Spanish, magnolia blossom skin, coal black hair. She was also having some problems with her marriage.

Monique and Consuelo were both very nice to me

and

I was friendly with them. So I invited them to lunch; they hadn’t

known each other before. The conversation was ‘Mon mari est un

grand aviateur et un grand écrivain’ and the other one said ‘mon

mari est un compositeur’ and they nattered on and then they looked

at me and they said ‘mais Isabel, tu ne dis rien’ and I said

‘mais je n’ai pas de mari’!

When I went to the opera I didn’t know anything about it, and I had a seat in the front row, one of the most expensive seats, which Monique got me. I sat there meticulously reading the libretto! Luckily I went back to Salzburg the next year and they did Don Giovanni again and this time I heard the music.

By this time at least you knew what was going on.

Yes, because Pierre used to write books about performances, little books about the plots, the themes, what they symbolised. Don Giovanni was one of his favourite ones, and then Berg.

Lulu

Yes, there was plenty to say about that. It was very obscure, very psychological, not the misunderstandings of cross-starred lovers.

In Salzburg I met the Schusters. Sir Victor was a great musician. He almost became a concert pianist. He married his wife who was a Scottish lady, the one who was the cousin of the Queen, of an impoverished noble Scottish family, because she was a keen musician, a violinist. He was the son of a Jewish financier and her family was aristocratic but their shared love of music brought them together. So I met Sir Victor and Lucy and their daughter Fifi who was seeing Blanche.

Other clients of Blanche were Benvenuto Sheard and Sherbun Sidéry. Sherbun was a précieux; he was charming. Nuto with his fussy manner would correct my French. He always had that pedantic thing which was terribly off-putting and Sherbun who was a queer but a kindly man went out of his way to say nice things to me to make up for Nuto’s taking me down.

I didn’t realise that was when you met them all.

Yes, and also Pierre Jouve’s son Olivier who was studying to be a doctor; he was there too. While we were in Salzburg, Blanche took Olivier and Fifi and me on a little trip to Vienna. She wanted to visit Freud who had cancer of the throat. We went to the opera and saw Twilight of the Gods. It went on for 4 hours, I think. I felt as though a steamroller had been going back and forth.

But Blanche was very moved after she’d seen Freud and said goodbye to him. She wasn’t actually analysed or treated by him but she was very much following his teachings and she had been to his lectures. She said she had a lot to bear, and he said, ‘ah mais vous avez des épaules.’ She had tiny little sloping shoulders!

Another client of Blanche at Salzburg in 1936 was Bianca Loewenstein. Brought up largely by her Jewish grandmother in Florence, she had studied sculpture. She and her husband Prince Leopold had to leave Bavaria when Hitler banned the Catholic Youth organisation run by Hubertus, Leopold’s brother.

Bianca’s mother Hetta von Kaufman-Asser, was known as ‘the Red Countess’ because of her important Salon in Berlin in 1918. She had known Pierre and his first wife in Switzerland during WW1 when they were pacificists and she was working with the Red Cross. She disapproved of Pierre’s marriage to Blanche. However, in following her great causes, she had neglected Bianca whose father, Count Treuberg, she had divorced soon after Bianca’s birth. Blanche helped Bianca with her emotional and family problems while Sir Victor Schuster did his best to help her financially as her husband’s money was inaccessible in Hitler’s Germany. Bianca in turn brought clients to Blanche and helped look after Fifi Schuster.

At the end of the festival Blanche and Pierre set off with Bianca for Sils Maria in the Swiss Engadine. Isabel, Nuto and Fifi were to go there by train. However, they received a pneu bleu message to say that the Jouves had had a motor accident, probably because the chauffeur was confused about which side of the road he was supposed to drive, (the law was different for different parts of Austria till the Germans invaded), and to meet them near Innsbruck. Blanche hurt her back, an injury which continued to plague her in later life, and the car needed mending, so everything was held up for a few days. Isabel and Bianca went walking in the countryside wearing their Tyrolean costumes: white muslin blouses, black velvet waistcoats and full, coloured skirts they had bought in Salzburg. Isabel was amazed when the local country people they met went down on their knees and kissed Bianca’s hand. The Treubergs came from Southern Bavaria, not so far away, and the Austrian peasants recognised a princess when they saw one. She was very tall and stately with ice-blue eyes and long blond hair in plaits round her head. Isabel felt like Alice in Wonderland.

Isabel had to get back to Paris to her mother so she never made it to Sils Maria in the Engadine. But Blanche, when she returned from there, agreed to see Isabel as a patient. Pierre’s comment? “Elle est barbare, mais elle a de jolies jambes!”

Romeo and Juliet

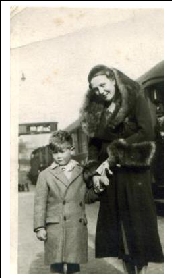

Desmond Ryan at Moncourt (circa 1970)

At Easter 1937 we (Fifi Schuster and Isabel) travelled on to Avignon to meet the Jouves at the Hôtel des Papes. The aim was to stay there and visit the Palais. Sitting in the reception area when we came down to dinner was a man with googly (prominent) blue eyes, who stood up and bowed very formally to Fifi, saying, “Miss Schuster, I believe”. Fifi introduced me to him. It was Desmond Ryan!. The Jouves came down and we all went into dinner together. Fifi got really wide-eyed. Not only was I joining the Jouves but Desmond was as well. “Ooh, I know about him”, she said, “I heard about him from Bianca and Sherbun. He’s got trouble with his wife and he drinks too much.” Sherbun Sidery had brought him over to Blanche to see if she could help him with his nervous problems.

He looked at one with great meaning in his eyes, and his eyebrows would pop up, but he stuttered rather, so that one was waiting for a long time, fixed with the gaze, before what was being said came out. One felt one had to encourage whatever it was that was being said.

We visited the Pope’s palace: that is we all went and gazed! I’d learnt this trick; one had to do a lot of gazing; one had to react to things; it was very new to me; ordinary people just chatted but no, round the Jouves one had to have reacted and thought and experienced something before one put it into words. The Jouves had a soirée once a week on a Thursday. It was a salon to which would come friends, musicians, philosophers, poets and visiting people. Blanche encouraged me to come to that. I guess good-looking young women didn’t do harm. After a certain time - well spaced out - les petits verres would be passed round by the good-looking girls to inspire the brilliant men to further flights of conversation. That was where I learnt the idea ‘never speak unless you have anything worthwhile to say’. That’s why I never spoke. I learnt a lot of French by listening. Once I started speaking, the French were astonished. Some bon mot of a French philosopher coming from the mouth of a South African!

So we gazed at the Palais des Papes until Pierre said ‘Aaah, c’est du Shakespeare pur, n’est-ce pas, Blanche’. Desmond was wooffling and kerfooferling, he hadn’t got used to this sort of routine‡.

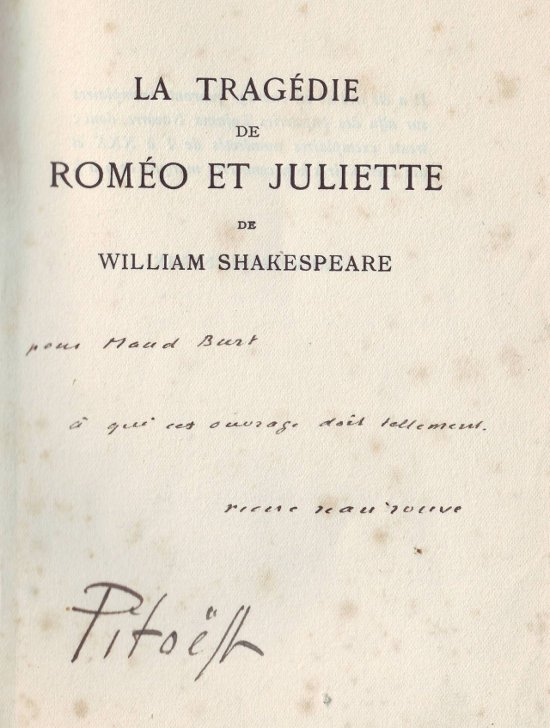

Doubtless Pierre would have been thinking of his French version of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet which appeared that year. (As Pierre didn’t speak much English, Blanche and Maud Burt had done the actual translating and Pierre had turned the literal French into poetry.) Appropriately, Desmond and Isabel started a liaison that weekend which had something of the Montagues and Capulets about it as his family were Canadian Irish, pillars of the Roman Catholic community, socialites and heavy drinkers, and hers were South African Scots, leading members of the Presbyterian church in Durban, and tee-total.

When the play was performed in Paris, Pierre gave Isabel tickets and she took Desmond. In the interval they headed for the bar where they stayed, Desmond opining that he didn’t think Shakespeare could be translated successfully into French. Isabel felt terribly embarrassed when Pierre appeared, white as a ghost, and saw them there. “Ah,” he said kindly, “The young lovers are snatching a moment together!”

Une Drôle de Guerre

The Salzberg festival

did not

take place after Austria was annexed by the Germans. Instead, in

August 1939, the Jouves went to the music festival at Lucerne, in

Switzerland, where Toscanini was conducting. At the end of the month, however,

they became increasingly worried by the threat of war between France

and Germany, and Blanche was concerned for the safety of Isabel and the

other foreigners in her entourage who depended on her. Isabel had not

gone to Lucerne this year as Desmond was taking her up to Megeves in

the Hautes Savoie where they were to be joined by the writer

Norman Douglas, at a restaurant with a very good chef, known only to a

few. Blanche sent Isabel a pneu bleu asking her to wait

for the Jouves at Combloux, near the Swiss-French

border, till they could decide on a safe plan. When the Jouves

arrived with Bianca, Fifi and Benvenuto Sheard, their chauffeur

was immediately called up to do his service militaire.

We got as far as Combloux on the border with Switzerland, where you take the train to Mégèves. Bianca, Fifi and Nuto were there with Blanche and Pierre. Coming back from the Lucerne music festival at the end of August they’d got stuck at the border. Everything was in confusion. Hitler was threatening war with Poland, and Combloux was in a zone militaire, which was under orders to prepare for military action. We had to stop there and find out what was happening: which trains would be going and where to: were foreigners allowed in. War preparations were starting. The hotel windows, which looked out on a magnificent view of Mont Blanc, were painted blue to dim their light.

Werner had rented HG Wells’ villa, Loupidou, near Cannes, for friends who hadn’t come, and he’d told Bianca she could use it. The Jouves’ chauffeur had gone, so it was arranged that I should drive them to Provence while Bianca took Fifi and Nuto on the train. Bianca could persuade people to do anything; she was fluent in German, Italian, English and French. Not only did she get them onto a train but the guard actually proposed marriage before the journey was over. He said: I know you’re a fine lady but if ever you’re in worse trouble than this, you can always count on me. She put it over that she had these two imbéciles to look after. With the war and everything Nuto and Fifi were looking a bit shell-shocked.

The Jouves had a beautiful new car, a

Talbot with a powerful engine and automatic gear change. Instead of

the clutch, you changed gear with your finger using a lever attached

to the steering wheel. 1 2 3 4 . Backward and forward for Reverse.

This was very easy, luckily, as not only was I driving the car but I

was also looking after Bianca’s 6 year old son, the young prince

Rupert. I’d never been near any children in my life, other than

Rupert himself whom I’d met when I stayed with his parents in

Cannes in 1937. The boy was in a state of shock without his mother.

Kipling came to my aid. I told him Jungle Stories.

The villa at St Mathieu de Grasse was an old farmhouse which HG Wells had modernized with one of his girlfriends. It had an imitation fireplace with the inscription: Two lovers built this house which made Pierre laugh. The servants were all laid on. The cook had a son who was about the same age as Rupert. Bianca and Nuto and Fifi arrived, having got out of Combloux. That was the first of September. But nothing happened, no attack came; the Germans concentrated on the fifth column propaganda -undermining people’s desire to fight. The idea was that we should join them and fight the Russians; the Germans didn’t want to fight us. They wanted to keep us quiet while they went east.

The domestic front, however, was not so peaceful. A minor war was taking place between Pierre and Desmond, a sort of family quarrel.

There was a clash of personalities. Pierre tended towards spirituality and disapproved of the younger man’s bon vivant lifestyle. Desmond’s idol was Norman Douglas, the great classicist and travel writer who loved food and wine. He had visited them all at the villa. Desmond found Pierre occasionally pompous and felt that he didn’t sufficiently appreciate Blanche and all that she did for him‡. Now the underlying tension was coming to the surface because Desmond was jealous of Pierre using me as his chauffeur.

Pierre loved motor cars. He had been seduced by Madge Molyneux-Seal who drove him around in her 2 seater MG Sports car. Here in Grasse he liked me to take him for a drive every day in the wonderful countryside of Provence. But one day Desmond in a fit of pique decided he would show Pierre that he could drive and tried to back the car out of the garage, despite Bianca’s best efforts to stop him. His eyesight was weak and he probably wasn’t sober with the result that he scraped the paintwork of the Talbot along the garage wall. Pierre appeared, singing the praises of his beloved car, to find Bianca leaning nonchalantly against the mudguard. He waited for her to move but as she showed no inclination to do so, he went round to the other side and got in. I took him for his drive and when we got back he got out and went straight into the house so we were able to rush off to a garage to get the car repainted!

Pierre got his revenge, you might say, some time later. Blanche had gone back to Paris to prepare things for Pierre’s return. When she was ready, Desmond and I drove Pierre and the Talbot up to Paris. After our long journey we arrived in the evening in Auxerre. In the blue light of wartime we passed Picasso’s sculpture of a Bull’s Head, made with a bicycle seat and handlebars.

In the restaurant where Desmond happily anticipated a gourmet dinner, Pierre ordered for himself nothing but a plate of tinned peas. Desmond felt this as an insult and never forgot it. But perhaps at heart he accepted the rebuke for, after all, he did name his second son Pierre after his godfather.

After the evacuation of British troops from Dunquerque Isabel and Desmond hurried back to Paris to lend their support. They never imagined the Germans would actually invade it. Nobody anticipated the speed of the Blitzkrieg.

We got to Paris in the middle of May 1940. It fell to the Germans on the 14th of June: everything happened quite quickly. We just got up to Paris in time to leave again.

I remember Blanche wanted to be driven to Notre Dame to pray every day from her place in the Champs Elysées. It was very grim because all the churches had the windows taken out, and sand-bags had been put all round to try and protect them in case of bombing; they were all stripped for the war. I said, “At least they haven’t bombed it”. Blanche turned on me and said, “A church without spirit is just a mass of stones anyway”. She was getting very depressed about morale in Paris. People were not fighting, they’d given in to all the propaganda and innuendo. I know Maud Burt believed it. She knew a lot of spiritualists in Paris and many were fifth columnists working for Hitler, himself a great follower: he had the spiritualists tell him which was a good day to attack and which was not. Of course the strongest argument the Germans had was ’Help us fight the Communists who are going to take your money. We’re not going to take your money, you ought to support us.’

There follows the Flight from Paris by Isabel and the Jouves which is on the website.

Some words by

Bron Grillo

From what my mother has told me, Maud Burt played an important part in the life of the Jouves. She and Blanche came from a generation of ‘strong’ women like Bianca and Isabel’s mothers. She comes over as a determined Englishwoman who was not interested in men but had a flair for good cooking and home-making. She had a high opinion of Blanche, who was not at all domestically minded but whom Maud considered to be very intelligent, more even than Pierre, and a most competent professional. It was she who insisted Pierre marry Blanche as it would have given her inferior status professionally in the twenties to be seen merely as his mistress.

The three of them had bought land outside Paris to build retirement houses but sadly the war forced Maud to return to England. As she had spent her savings she had to live with friends.

La Tragédie de Roméo et Juliette, traduction intégrale par Pierre Jean Jouve et Georges Pitoëff (Gallimard, 10 juillet 1937) :

"Les auteurs doivent des remerciements à Madame B. R. Jouve, ainsi quà Mademoiselle Maud K. Burt, directrice des Études Britanniques à Paris, pour leur collaboration au travail de la traduction."

Lien avec un site consacré à l'école de Beauvallon

Isabel heard about Marguerite Soubeyran’s important work after the war. In 1952 she bought a cottage at Alba in the Ardeche, about 45 mins drive from Dieulefit and sent son Bene aged six to Beauvallon following in the footsteps of his half-brother, Sebastian.

Mention of Marguerite Soubeyron earned her much respect among the artists and writers of the Alba colony, who were of many nationalities.

Sebastian 1939

At the fall of France Blanche was sending lots of refugees to Dieulefit in the Drome where her friend Marguerite Soubeyran ran a mixed, progressive boarding school for children with behavioural problems. In 1939 Desmond was officially living with his American wife, Leona and their son Sebastian, aged 6, in Monaco but spending a lot of time away with Isabel. Seeing the problem, Blanche advised him to send Sebastian to the Beauvallon school at Dieulefit where Marguerite was used to welcoming children whose parents were having problems. .

Leona 1938

The German approach to Paris happened so fast that Isabel and Desmond fled South with the Jouves and Maud (see The fall of Paris) with no time to make plans. After the Armistice of 22 June 1940 Desmond as a young Englishman of military age had to get out of the country quickly. He and Isabel managed to get on an Egyptian merchant ship sent to pick up refugees at Marseilles. After a long and difficult journey dodging submarines they reached Liverpool. Leona meanwhile made her way to Dieulefit where Marguerite looked after her until the following year when money was sent for her and Sebastian to escape through Spain to Bermuda where Desmond’s mother was.

Haut de la page

Site Pierre Jean Jouve

Sous la Responsabilité

de Béatrice Bonhomme

et Jean-Paul Louis-Lambert

Ce texte et toutes les photographies © Isabel Ryan and Bron Grillo

Première mise en ligne : 10 août 2010, premières corrections : 2 octobre 2010

Nouvelles versions corrigées : 27 octobre et 13 novembre

2010

Page réalisée par Jean-Paul Louis-Lambert

Home