Jouve International

Domaine anglais

The poet as engineer of truth:

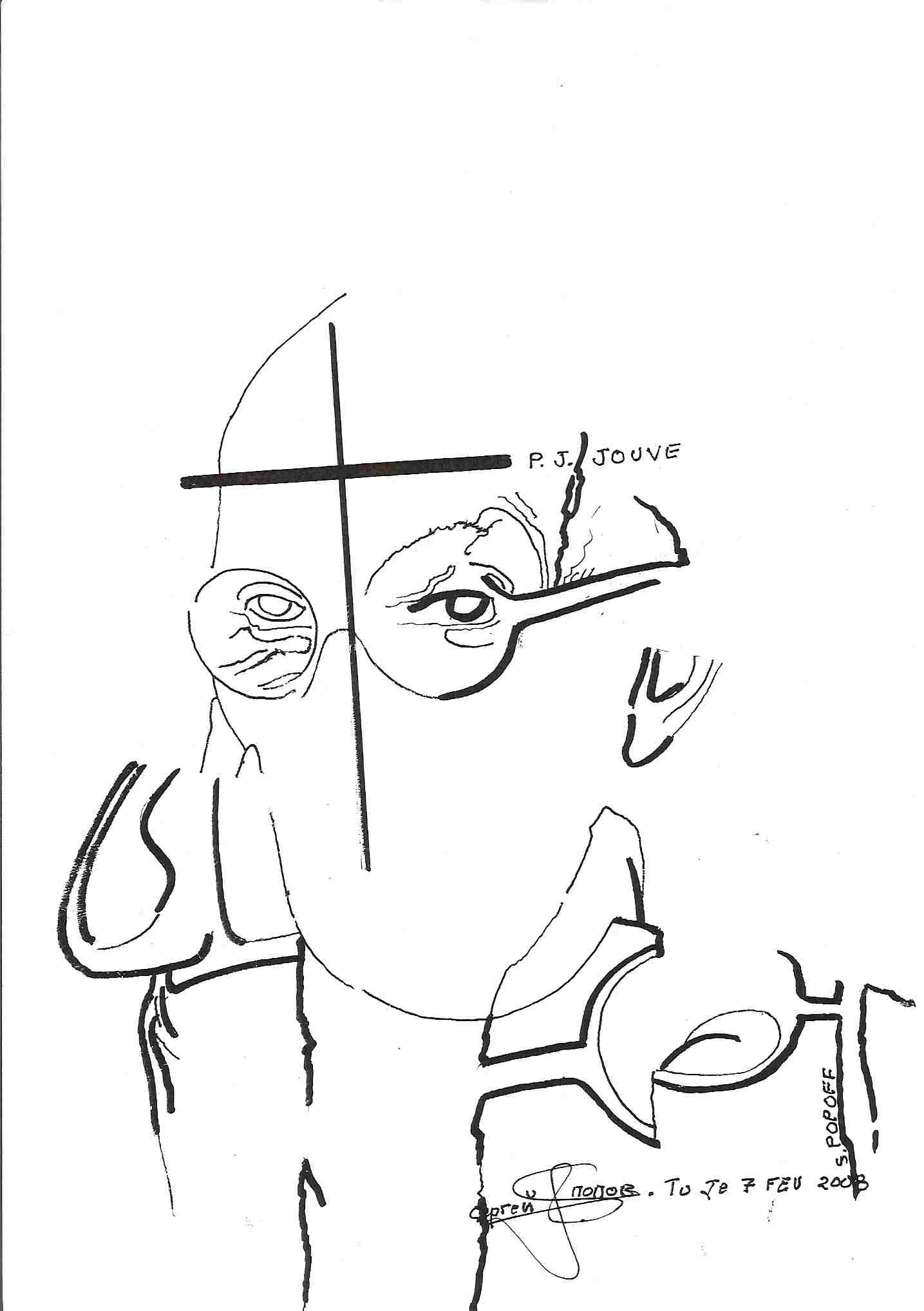

Pierre Jean Jouve

par Michael G. Kelly

II. Three readings

I wish to discuss

three examples of the poet Jouve as ‘symbolic’ engineer. Each corresponds to

what might be called a theme in his works – which in each case coheres around a

name that is also an image or a fund of images. It is in this weak sense that I

understand Jouve’s insistence upon the idea of symbol and symbolic system. The

‘symbol’ comes not so much to represent something else as to condense otherwise

unformulable complexes of thought and intuition. Supersaturated, they suggest

rather than speak volumes. Their names become objects of contemplation, the

intimation of the proximity of sense. For Jouve this weight of sense in objects

is the basis of chant itself:

Que le monde

Dans l’espérance, que le sein très lourd de la vierge

Et non touché par le soleil ! ainsi mon monde

Est mon chant ô cher cœur.

Truth is a personal world in excess. The primary excess is the capacity to hold down fundamental meanings, an excess of signifying power. One familiar human strategy is to source fundamental meanings in the features of a loved person. Jouve embodies his literally ‘significant other’ under the name Hélène, a kind of twentieth-century, freudianised Beatrice:

Hélène first appears in the prose text Dans les années profondes (M.C.), where the adolescent Léonide is initiated as a poet through what he perceives or constructs as her sacrificial death in the throes of their consummating, ‘capital’ encounter. But the would-be poet’s first vision of Hélène already has her as the symbolic conduit of literary fantasy:

The represented human figure is a condensation of the exemplary Italian countryside. Further on, the figure is reduced to an object, symbolic to a degree verging on the fetishistic:

La robe […] Les membres […] Sa poitrine […] son

visage […] L’extraordinaire était ce qui surmontait son visage; elle avait une

masse, un édifice de cheveux; une chevelure, à la fois pleine comme un nid de

serpents et mousseuse ou rayonnante comme du soleil […]. Cette chevelure, toute

pareille au Phénomène Futur, je ne la connaissais pas; je ne l’avais jamais vu;

je ne pensais pas qu’elle pût exister.

Two pages further on, the depersonalisation is complete. The figure as perceived has been transformed and condensed into a kind of cosmic signifier:

Death, when it arrives, is an additional, sacralising element in this process – freeing up the object as a discrete unit of sense, and facilitating the drive towards the intelligible extreme in which Jouve identifies exemplarity with truth:

La poussière de la mort t’a déshabillée même de l’âme

Que tu es convoitée depuis que nous avons disparu

[…]

Il fait beau sur les cirques verts inattendus

Transformées en églises

Il fait beau sur le plateau désastreux nu et retourné

Parce que tu es si morte

The experience of the sacred, inextricable in the typical Jouvian manner from a psychosexual problematic, relies upon an evacuation of the ‘human as material object’. This renders it as matière céleste – the perfect eloquence born in the sense of the self-evident:

De sentir la main savoureuse du ciel

Fouiller la place vide où se trouvait le cœur

[…]

Adorable ruban que la chair se déroule

[…]

Partout d’érectiles seins puissants

Font escorte dans la pleine lumière des allusions

The liberation of objects in their accession to the symbolic, their primary establishment as signifying surfaces to the poetic eye, allows for their permutation and superposition. One frequently-occurring example of this is the superscription of the landscape with the terminology of the (generally female) body. While the corps-paysage effect allows for the figured generalisation of the libidinal – the signifiers of sexual union becoming ubiquitous – the establishment of the object as mobile unit of sense mirrors the general-truth claims of Jouve’s chosen discourse:

The establishment of the sacred is, following Mircea Eliade, at its most elementary a question of the division of space: “Pour l’homme religieux, l’espace n’est pas homogène; il présente des ruptures, des cassures: il y a des portions d’espace qualitativement différentes des autres.” (Eliade 26) The recognition of the human rootedness in Eros-as-drive-towards-unity is reconciled with this differentiated spatiality of the sacred in the rearrangements of a world become language at which Jouve is adept:

Dans ces forêts insignifiantes et d’opprobre

Sous un ciel bleu l’eau suceur de la mer;

et si troué par le sein de cet air

Le clocher italien durement illustré

Car il nie l’étendue complète de terre. (N.S.S. 169)

It would however be misrepresentative of the experience of reading a collection such as Sueur de Sang to suggest that its treatment of sex and the sexual is constantly allegorised or scrambled (to speak of Eros is already to choose to allegorise). More commonly the body is depersonalised or anonymous, a torso or trunk over which the text chooses an itinerary from one of a number. A question which arises in reading work with this feature relates to the effect of repetition or insistence on the emblematic quality of a given object. ‘Sein’ is everywhere invoked; ‘aisselle’ can be involved here either as a kind of optional extension or as a negative pole to this – whereas convex sein is statuesque and pale, cavernous aisselle is frequently associated by Jouve with ‘poil’, ‘odeur’ or ‘sueur’. A symbolic treatment of the body is complicated by the inclusion of the non-localisable or fluid. The signifying power of sang is far less contained, more ruggedly metaphorical, than that of an external topological feature. It can denote a physical substratum, as would seem to be the case here:

[…]

Et que tu te souviennes des fonds saigneux … (ibid.171)

Elsewhere it has a connotative overlay of suffering or / and visceral intensity, these being uppermost where Jouve merges ‘erotic’ and ‘religious’. Although there is an argument to be made that this merging is in fact everywhere in the Jouvian text – and for Jouve the two discourses were theoretically inseparable, being coterminous in the human imperative of ‘unity’ in the face of death – the link is in some instances foregrounded by the use of a polyvalent imagery. Thus ‘blessure’, for example, localises ‘sang’, gathers together the surface and the internal, the sacred object of adoration and the sexual object of taboo (albeit that the semantic chain ventre – orifice – fente and the modulations of ‘ouverture’ are in fact insistent occurrences in the work). Consciously this allows Jouve to structure his mystical and social preoccupations around a vertical axe (extremity being prioritised) – thus Prostitutes are Christ-like (in addition to being abject, as in Baudelaire) through a commonality of the blessure publique. Jouve also cultivates the comparison between prostitute and poet (see p. 4, supra). The prostitute is of course that poetically satisfying compound of an abstract principle, a public function, a flesh-and-blood person and a lost cause:

Le regard inhumain les soleils hébétés

J’ai traversé vingt fois sous un homme la mer

Le sol gras de la mer et le bleu et les moires

To say as much is admittedly to subject Jouve to a procès d’intention. The one serious justification one could have for so doing, is that the poet himself defines his poetic project in terms of an intellectual (or at least conscious) engagement with the unconscious. Art, which ever remained his stated objective, must on this view engage with the unconscious rather than be colonised by it. Intentionality reaches a new prominence as it explicitly acknowledges the lately-articulated challenges to it. Jouve qua disciple of Freud pays more attention to the primary message on the primacy of libidinal energy, than to the Freudian mechanisms whereby this energy becomes manifest through the individual subject. He might rightly argue that in confronting the physicality of Eros head-on he had forestalled the processes of sublimation which Freud purported to describe in other writers. But to what extent then are the strategies of generalisation and diffusion (not dissipation) of the erotic throughout the Jouvian symbolic universe the signs of a new sublimation – towards the underlying goal of a unified poetic vision? Perhaps this is the risk incurred with the poetic aspirations to density and absoluteness in language. It seems unavoidable so long as presence (another formulation or metaphor of these aspirations) is sought to be attained through representation. Is it that the ambition of a poetry that is both religious and vital cannot but precipitate its subject out of the ‘symbolic order’, or into compromises which look like inconsistencies?

With this reasoning again we risk too tidy a conclusion. The ‘monde plus vrai’, the excess of poetic truth of which Jouve is aware and covetous, is as much about trying to circumscribe contradiction as to resolve it. The conscious invention of a symbolic system seeks far less to be logically foolproof than to be capable of multiple readings, thereby capable of offering some greater or lesser sense to each reader engaging with them.

The Stag (Cerf) is the best-known of Jouve’s creations – and cornerstone as such for numerous poetic texts. Jouve makes the compound nature of the Stag explicit, defining it as:

If the Stag is thus in fact a plurality of ‘symbol’ as Jouve understands that term it nevertheless remains a coherent figure, an organic compression of meanings and vectors in the one signifier. It is also more than a verbal mark – summoning up an image, and visualising half-forgotten continuations around nature, majesty, sacrifice. Capitalised, it declares an expectation of conventionalised, ceremonious recognition. It demands to be read expansively as a public object, having been introduced in lower case as a compound of private significance:

Pelotonné dans la chaleur de l’unité

Secrètement à genoux avant l’aube

Sans haleine dans l’épaisseur des montagnes

This stag concentrates the subject’s desire for death, objectifies and becomes a vessel for it – establishing its conventional credentials as bouc émissaire:

[…]

La balle ce sera votre ultime désir

Et tout votre destin

Projeté dans le destin sublime du cerf

Tandis que le sang très sombrement vous récompense.

The stag is then drawn as a hypostasis of the self, a figuration of the shadow-life of the subject who experiences humanity as desire (in self-consciously psychoanalytic terms):

De soi, du plaisir de tuer le père

Et du larcin érotique avec la sœur,

Des lauriers et des fécales amours.

The elusive and hunted beast, in answering the prayers to appear and be killed, is, in that anticipated moment, the frame within which conflicting registers and qualitative polarities of need find momentary unified expression. This is a symbolic and textual feat, not a logical one. There is a co-presencing being sought, as distinct from a full reconciliation. The figure generating meaning, the symbol of the stag, controls the ‘malgré. Poetic symbol is the space within which the proviso can be repressed:

Apparais dans un corps

Chaud, toi qui passes la mort.

Oui toi dont les blessures

Marquent les trous de notre vrai amour

A force de nos coups, apparais et reviens

Malgré l’amour, malgré que

Crache la blessure.

The projection of a cluster of truths onto a fragmented image, delivered in the idiosyncratic movement of the poetic lines – broken, while retaining fluidity - contrives to make of the Stag a facilitating sign; much more an ordering principle than a referential shot in the dark. The last quote above is from Lamentations au Cerf – which names this ordering principle in its title, but nowhere else. The stag is an addressee, an objective which allows the poem to draw itself out into a complicated but not chaotically dissonant form. This is one textual value of the symbol/locus – its generative capacity. Another is its radiating strength as oriented towards the reader. The stag functions like a figurative key to an abstract painting, a concession to a socially-ratified form of perception. But at its most transparently verbal it functions like a name for something else. The symbolic life of Jouve’s truth can be seen to have emerged from a continuum of abstractions, or totalisations. Having resourced himself in some of the grand discourses on the way to a personal truth, this was not avoidable. In any case, Jouve maintained a quite rigorous division of theoretical expounding (if not vocabulary) from poetic practice. Where the two come together – that is, the non-figurative and the poetic – seem to this writer to be in what Jouve terms ‘le thème Nada’, on which a few concluding remarks.

Nada is, with apologies for the tautology, the degré zéro of Jouve’s symbolising progress towards poetic truth.

Jouve concretises the category absence/negation by applying the resonant

foreign term, taken from a line of

No quieras ser algo en nada

Ne cherche à être rien de rien ).

Nada is an antagonistic pair:

Nada becomes a way of thinking – poetically:

Le désir de la fuite et celui de la terre

L’excrément des villes c’est l’amour de l’or

Le désir de la jeunesse est l’appétit du cimetière

[…]

Et roulant sur la noire paroi de vertige

De ce monde aboli : tu approches de l’Un

The truth conveyed in this poetry is a poetic truth, just as its ambitions are the canonical ambitions of poetry. Jouve unifies and contradicts – he prefers his more vivid Truth to the realities of which he partakes; that Truth is one where absolute and intelligence coincide in the mystery of presence (carnal-physical-natural-divine-symbolic). It is arrested momentarily in language, before disappearing again into the surrounding silence:

De faim! Mais c’est encore un décor de langage

Que brise ton baiser ô Sang. Et sang tué.

Readers in English will be interested to know that a Selected Poems, with translations by the late David Gascoyne, has recently been published –

Pierre Jean Jouve, Despair Has Wings. Selected Poems (tr.

David Gascoyne, ed. Roger Scott).

Jouve. Les Noces (1928) suivi de Sueur de Sang (1933). Poésie/Gallimard,

1966. [N.S.S.]

_____. Dans les années profondes (1961); Matière céleste (1964); Proses (1960). Poésie/Gallimard, 1995.

[M.C.]

_____. Diadème (1949) suivi de Mélodrame. Poésie/Gallimard, 1970.

[D.M.]

_____. En Miroir (Journal sans date). Mercure

de France, 1954. [E.M.]

_____. Défense et Illustration. Charlot, 1946.

[D.I.]

_____. De la Révolution comme sacrifice, 1944.

L’Herne, 1971.

_____. Paulina 1880. Mercure de France, 1959.

Baudelaire. Les Fleurs du Mal. Poésie/Gallimard.

Michaux. Plume suivi de Lointain Intérieur. Poésie/Gallimard.

Yeats. Collected Poetry. Everyman.

Kelley and Khalfa

(eds.): The New French Poetry. Bloodaxe, 1996. [K.K.]

Bonnefoy:

‘Pierre Jean Jouve’ in La Vérité de

Parole (Essais), Mercure de France, folio essais, 1995. [Bonnefoy]

Haut de la page

Home